Treponema pallidum

Taxonomy

Brief facts

Biology of Treponema pallidum

Evasion of host immune defenses

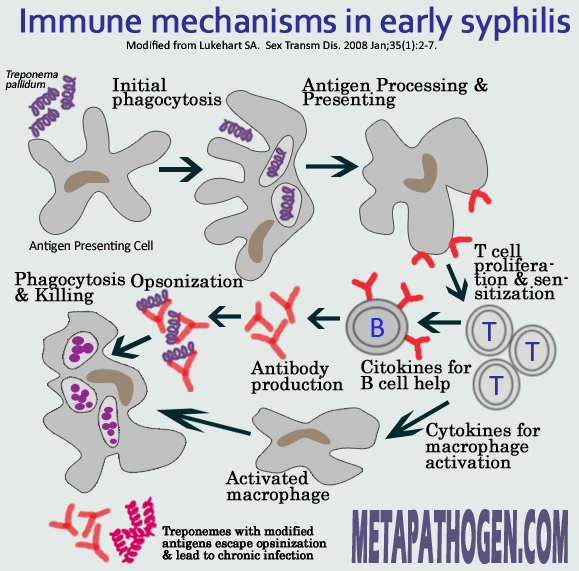

Immune response to early syphilis

Immune response to early syphilis

Stages of syphilis

Treatment

Features associated with HIV/syphilis co-infection

References

Taxonomy

Treponema pallidum belongs to the only order Spirochaetales in class of bacteria Spirochaetes. All spirochetes are helical or spiral shaped microorganisms. Spirochetes are highly motile and propel themselves in corkscrew manner by rotating around their longitudinal axes. These organisms can swim easily through gel-like materials that hinder most other flagellated organisms, which allow some spirochetes to occupy unique ecological niches, such as sediments in pond and lake bottoms, the guts of certain arthropods, and the rumens of cows and sheep. The arrangement of spirochete flagella is also unique among the bacteria. The flagella are inserted subterminally at each end of the cell, wrap around the protoplasmic cylinder, and usually overlap in the center region. They are located between the protoplasmic cylinder and an outer membrane-like structure called the outer sheath and called endoflagella or periplasmic flagella. All spirochetes are resistant to the antibiotic rifamycin. The order is divided into three major families Brachyspiraceae, Leptospiraceae, and Spirochaetaceae. Treponema pallidum is classified into Spirochaetaceae, the family that apart of genus Treponema also contains genera Borrelia (contains causative agents of Lyme disease and relapsing fever), Cristispira (found in digestive tract of bivalve mollusks), Spirochaeta (free-living spirochetes), Brevinema (infectious in some animals), Brachyspira (pathogenic in swine and chicken), and Spironema (found in mosquito).

Borrelia burgdorferi, Lyme disease spirochete taxonomy, facts, pathogenicity, and bibliography at MetaPathogen

cellular organisms - Bacteria - Spirochaetes - Spirochaetes (class) - Spirochaetales - Spirochaetaceae - Treponema - Treponema pallidum - Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum

Brief facts

Trepanematoses caused by Treponema pallidum

There are several devastating diseases collectively called trepanematoses that are caused by subspecies of Treponema pallidum. Syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease (STD) caused by Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum, is best known, most studied, and most widely spread. The other non-venereal treponematoses are: yaws (Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue), bejel (Treponema pallidum subsp. endemicum), and pinta (Treponema pallidum subsp. carateum or species level Treponema carateum). They differ in their modes of transmission, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations from venereal syphilis, which is said the only trepanematosis that can lead to Central Nervous System (CNS) involvement and congenital (transmitted from mother to child during pregnancy) disease. However, like syphilis, they have a chronic relapsing course, prominent cutaneous manifestations, and can result in gummatous destruction of bone and cartilage.

Millions of infected people

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that there are 12 million new cases of syphilis per year, and the total number of cases of yaws, bejel, and pinta (the endemic treponematoses) is approximately 2.5 million.

Columbian hypothesis of origin of syphilis

At least three hypotheses about origin of syphilis in Europe were advanced. Most popular and best supported by historical, archeological (skeletal remains), and molecular phylogenetic studies is so-called Columbian hypothesis, which suggests that original treponemal disease spread from Africa through Asia, entering North America. Approximately 8 millennia later, it mutated to syphilis. Ample presence of the skeletal evidence of syphilis at the site of the Columbus' landing (Dominican Republic) suggests that the Columbus soldiers got infected there and then transmitted the disease to the Old World when they returned in 1462.

First epidemic of syphilis occurred in Europe in 1495

King Charles VIII of France invaded Italy in 1495. Within months, his army collapsed and fled because of mysterious new disease (syphilis) that killed and weakened a great number of King's soldiers. Survivors then spread it across much of Europe.

Treponema pallidum was much more virulent in XV - XVI centuries

Judging by numerous historical accounts, syphilis in XV - XVI was extreremly unpleasant disease characterized by considerable morbidity and mortality. One of the most prominent symptoms described were huge ("like acorns") pustules or boils that emitted a horrendous smell, severe ulceration of the part of the body (often the genitals), necrosis of soft tissues, which could lead to soft tissue being eaten to the bone, and the rapid onset of the gummatous tumors typical of tertiary syphilis today.

Rapid decrease in virulence T. pallidum

In 5 -7 years that followed its first appearance, syphilis quickly changed from an acute, severe and debilitating disease to the milder chronic infection that is modern syphilis. This period is too short for any form of resistance to arise in human population by selection. Therefore, most likely, selective pressure was applied to the pathogen that led to adjustment of its virulence. Several authors have recently considered the evolution of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and it has been pointed out that STDs that decrease attractiveness of the host will inevitably repel his/her potential sexual partners. Moreover, severe illness accompanied with pain disables or distracts the sufferer from seeking out new sexual partners. Both of these two mechanisms would lead to reduced transmission of virulent strains.

Discovery of Treponema pallidum

Treponema pallidum was demonstrated under magnification in Berlin on March 3, 1905 by Schauddin and Hoffman. The discovery had come at the right time because syphilis was epidemic and presented a very serious health problem in all industrialized countries at that time. During the early 1900s, syphilis was estimated to affect ~10% of the population of the United States and Western Europe.

Famous persons suspected to have died from syphilis

Ernst Theodor A. Hoffman (writer, poet, composer, 1776 - 1822)

Nicola Paganini (composer, violinist, 1782 - 1840)

Arthur Schopenhauer (philosopher, 1788 - 1860)

Franz Schubert (composer, 1797 - 1828)

Gaetano D. M. Donizetti (composer, 1797 - 1848)

Heinrich Heine (poet, 1797 - 1856)

Mikhail J. Glinka (composer, 1804 - 1857)

Robert A. Schumann (composer, 1810 - 1856)

Ignaz Semmelweis (gynecologist, 1818 - 1865)

Charles Baudelaire (poet, 1821 - 1867)

Gustav Flaubert (poet, 1821 - 1880)

Bedrich Smetana (composer, 1824 - 1884)

Eduard Manet (painter, 1832 - 1883)

Alexis Emanuel Chabrier (composer, 1841 - 1894)

Friedrich W. Nietzsche (philosopher, 1844 - 1900)

Paul Gauguin (painter, 1848 - 1903)

Guy de Maupassant (novelist, 1850 - 1893)

Hugo Wolf (composer, 1860 - 1903)

Frederick Delius (composer, 1862 - 1934)

Back to top Nemose

Biology of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum

Morphology

T. pallidum is a small bacterium (0.2 µm in diameter and between 6-15 µm in length). The dark field microscopy is necessary to see it. The organism has regular, tight spirals and displays rotary, flexive and to-and-fro movements. Its body is surrounded by a cytoplasmic membrane enclosed by an outer membrane. A thin layer of peptidoglycan is sandwiched between these membranes to give added stability. The periplasmic space contains endoflagella that facilitate the characteristic motility.

Infectivity

T. pallidum is transmitted by direct contact, usually sexual. Infection is initiated when T. pallidum penetrates dermal microabrasions or intact mucous membranes. Studies have shown that 16 to 30% of individuals who have had sexual contact with a syphilis-infected person become infected. Actual transmission rates can be higher. The 50% infectious dose is estimated to be only 57 organisms.

Upon initial infection the parasites prefer to multiply at the point of entry causing the inflammatory response and formation of characteristic chancre. From the chancre the treponemes disseminate rapidly to the blood and lymphatics and make their way to different parts of the body including Central Nervous System (CNS). T. pallidum has been shown to induce the production of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) in dermal cells. MMP-1 is involved in breaking down collagen, which may help T. pallidum to traverse the junctions between endothelial cells and penetrate tissues.

The only known natural host of the bacterium is the human. Combined with transmission mode, this fact gives hope to a possibility of complete eradication of the syphilis in a future.

Challenges for research

Treponema pallidum cannot be cultivated long term (more than 100-fold ~7 generations) in vitro. In laboratory, T. pallidum can be only maintained by propagation in rabbits. Because of fragility of its outer membrane, researches are unable to modify the bacterium genetically in order to conduct experiments, which in many other bacteria clarified various aspects of their biology such as protein functions, mechanisms of virulence, and others.

Small genome

The genome of T. pallidum is much smaller (1.14 Mb) than that of many conventional Gramm-negative bacteria, for example, E. coli (4.6 Mb) and B. subtilis (4.2 Mb), and encodes some 1000 putative proteins.

Metabolic deficiencies

The bacterium lacks tricarboxic acid cycle enzymes and the electron transport chain. T. pallidum depends upon glycolysis as the sole pathway for the synthesis ATP. In addition, a pathway for amino acids and fatty acids synthesis as well as for metabolism of alternative carbon energy sources and for the synthesis of nucleotides and enzyme cofactors seems to be absent. These traits suggest that the bacterium derives most essential macromolecules from its host (enzymes for interconversion of amino acids and fatty acids as well as homologs of transporters for a variety of amino acids are present). Because the T. pallidum genome encodes no known homologs to porin proteins, it is unclear how nutrients are moved across the outer membrane into periplasmic space.

Slow multiplication rate

T. pallidum divides very slowly, doubling every 30-33 hours in vivo. In contrast, Nesseria gonorrhoeae divides approximately every 60 minutes, and E. coli every 20 min.

Limited stress response and heat tolerance

The lack of enzymes that detoxify reactive oxigen species such as catalase and oxidase makes T. pallidum vulnerable to oxygen. In a number of reports best survival occurred at low concentrations of oxygen (1-5%).

At least one its enzyme is unstable at normal body temperature. Heat therapy for late neurosyphilis was introduced in 1918 by the Viennese psychiatrist Julius Wagner von Jauregg, a discovery for which he later won the Nobel Prize in Medicine. He inoculated patients with malaria pathogen and 10 to 12 febrile episodes late, treated them with quinine. The high temperatures induced by this regimen, along with other methods of raising body temperature, presumably killed T. pallidum in the CNS. Doctors reported high percentage of complete or partial remission of general paresis symptoms (although the treatment killed about 10% of patients).

Back to top Nemose

Evasion of host immune defenses

For a long time researchers tried to explain mechanisms underlying the natural course of the syphilis: recurring clinical manifestations separated by prolonged asymptomatic periods. In early 1970s it was believed that treponemes cause specific or generalized immunosuppression and are resistant to phagocytosis by macrophages and neutrophils. Later studies showed, however, that initial immune response of host to treponemal assault, though slow to develop, is rather robust, and as treponemes reach peak numbers, macrophages begin to infiltrate the lesions resulting in rapid clearance of overwhelming majority of the parasites from the tissue. However, some portion of the treponemes remains untouched and continues living in the host causing a persistent infection.

Lack of endo- and exotoxins

The T. pallidum lacks liposaccharide (LPS), the endotoxin found in the outer membranes of many gram-negative bacteria. The attachment of T. pallidum to cells does not harm the cells (no swelling or indentation). The cultured cells survive for 5-7 days with actively motile attached treponemes in quantities up to 100 organisms per cell and remain viable. This indicates that cytolytic enzymes or other cytotoxins most probably do not play a role in syphilis pathogenesis.

Invasion of "immune-privileged" tissues

T. pallidum penetrates a broad variety of tissues, including so-called "immune privileged": the central nervous system, eye, and placenta, where there is less surveillance by the host's innate immune system.

Ability to maintain infection with few organisms

T. pallidum may also exploit its slow metabolism to survive in tissues, even those that are not immune privileged. By maintaining infection with very few organisms in anatomical sites distant from one another, T. pallidum may prevent its clearance by failing to trigger the host's immune response, which was speculated to require a "critical antigenic mass".

Lack of surface antigens

Outer surfaces of bacterial pathogens are the first bacterial component to encounter the host and are often the targets of host adaptive immunity. One of most prominent features of T. pallidum is that its cell has only rare integral proteins in its outer membrane, approximately 1% of the number found in the outer membrane of E. coli. The rare T. pallidum outer membrane proteins are likely to be very important in interactions with the host; for this reason, their identity has been the subject of intense research.

Low iron requirements, ability to obtain sequestered iron

Iron sequestration is one of the important defense mechanisms used by the infected host. The host's transferrin and lactoferrin proteins bind free iron making it unavailable to bacteria and impairing their growth. T. pallidum may be able to acquire iron from these host proteins. It may also overcome the iron sequestration by using enzymes that need metals other than iron as their cofactors. In addition it lacks an electron transport chain, which is made up of enzymes that use iron as a cofactor, which decreases its overall demand for iron.

Resistance to macrophages in subpopulation of the pathogen

Opsonizing agents are serum components, antibodies, or the complement protein C3b, which make the pathogen recognizable to macrophages via specific cell surface receptors. T. pallidum antigens, including Tp92 and TprK, have been shown to induce production of opsonic antibodies. Antibodies against the VDRL (Venereal Disease Research Laboratory) antigen, a complex of cardiolipin, cholesterol, and lecithin, also increase the phagocytosis of T. pallidum by macrophages. Majority of treponemes that multiplied in quantities at the site of initial infection usually are cleared by macrophages. However, a small subpopulation of the organisms persists and appears to resist ingestion by macrophages. This phenomenon suggests that opsonic antibodies do not bind these organisms, thus allowing them to survive in the face of active immune clearance.

Resistance to neutralization by antibodies

Besides opsonization, there are other functions of antibodies produced during T. pallidum infection. Antibodies developed against T. pallidum immobilize organisms and block them from binding the host's cells. Administration of whole serum and fractionated IgG from long-term-infected rabbits delays lesion formation in challenged rabbits, but lesions develop at the inoculation site within days of discontinuing the treatment. This demonstrates that specific antibody alone, while inhibitory to the establishment of lesions, is not sufficient to kill T. pallidum and prevent infection.

Orchestrated regulation of expression of antigens

Several genes that encode candidate outer membrane proteins belong to the tpr gene family which contains twelve genes that are divided into three subfamilies I, II, and III). The proteins encoded by tprF, tprI, and tprK are predicted to be located in the outer membrane. Most of the proteins encoded by the tpr genes (the Tprs) elicit an immune response in experimental syphilis. Antibody responses arise at different times after infection: anti-TprK antibodies are seen as soon as 17 days postinfection and are robustly reactive at day 30, while antibodies against the members of subfamilies I and II often are not detectable until 45 days after infection and reach peak titers at day 60. The time of development of antibodies to specific Tprs may reveal the timing of expression of the proteins that induced those antibodies. Regulation of expression of related proteins is referred to as phase variation and may be used by T. pallidum to down-regulate the expression of those Tprs against which an immune response has been mounted, while simultaneously up-regulating the expression of new Tprs, which are not recognized by the existing immune response. This strategy may help T. pallidum maintain chronic infection.

Antigenic variation of TprK protein

Recent studies identified TprK as a membrane-localized protein. The tprK gene and predicted protein amino acid sequences are characterized by seven discrete variable (V) regions that are separated by stretches of conserved sequences. Diverse tprK sequences have been demonstrated between subpopulations of every T. pallidum strain within single host. DNA sequence cassettes that correspond to V-region sequences were discovered in an area of the T. pallidum chromosome separate from the tprK gene. These cassettes are potential sequence donors and are presumed to replace portions of V-region sequences in the tprK gene. The TprK protein elicits both cellular and humoral immunity in infected animals. Antibodies to TprK that arise in response to T. pallidum infection are specifically targeted to the V regions. Very slight changes of the amino acid sequence in a V region can abrogate the ability of antibodies to bind the V region. Thus, the host immunity may eliminate organisms that express TprK sequences against which specific antibodies have been developed. Generating new variation in TprK may help pathogens to escape immune recognition and sustain the chronic infection.

Immune response to early syphilis